Even if his name doesn’t ring a bell, you’re no doubt familiar with René Magritte’s iconic imagery: the man in a bowler hat whose face is hidden by a floating green apple; the pipe with “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”) in script beneath it; the closeup of an eye with the iris replaced by a cloud-streaked sky.

The False Mirror, 1928. Photo by Eneas De Troya/Flickr.

But while hat tips to Magritte have cropped up everywhere from The Simpsons to The Fault in Our Stars, most people know little about the Belgian artist himself. Born November 21, 1898, Magritte kept a fairly low personal profile, especially in comparison to the outsize influence he’s had on Surrealism and Pop Art.

On one hand, that’s a shame, as his life was almost as fascinating as his art (he allegedly worked for a time as a forger; the friend he asked to “distract” his wife while he had an affair ended up in relationship with her). At the same time, this allows Magritte’s work to remain free from the cult of personality that has influenced the legacy of Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí, among others.

Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of Magritte’s paintings is that, with some exceptions, even the most fantastical scenes are depicted in a realistic manner. The miniature train emerging from the fireplace in Time Transfixed is, along with the painting’s wood floorboards, the marble mantel, and the moldings of the wall, rendered with a precision that makes the juxtaposition of the real and the unreal unnerving in a way that an impressionistic train wouldn’t be.

Magritte understood the power of unlikely juxtapositions to illustrate life’s myriad dichotomies. “If the dream is a translation of waking life, waking life is also a translation of the dream,” he noted, and for the program of a 1962 exhibition of his works he wrote, “A thing which is present can be invisible, hidden by what it shows.” While such statements taken at face value can be puzzling, even frustrating, his art makes them beautifully clear.

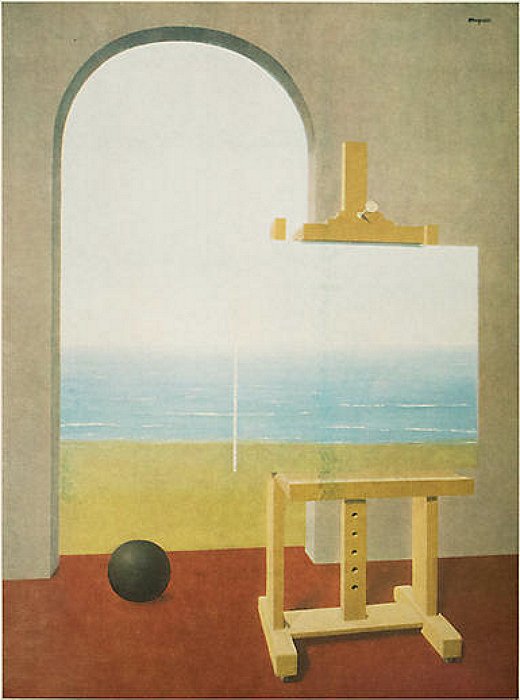

The Human Condition II, 1935. In a letter discussing an earlier version of this painting, Magritte wrote, “There is no implied meaning in my paintings, despite the confusion that attributes symbolic meaning to my painting. How can anyone enjoy interpreting symbols? They are ‘substitutes’ that are only useful to a mind that is incapable of knowing the things themselves.”

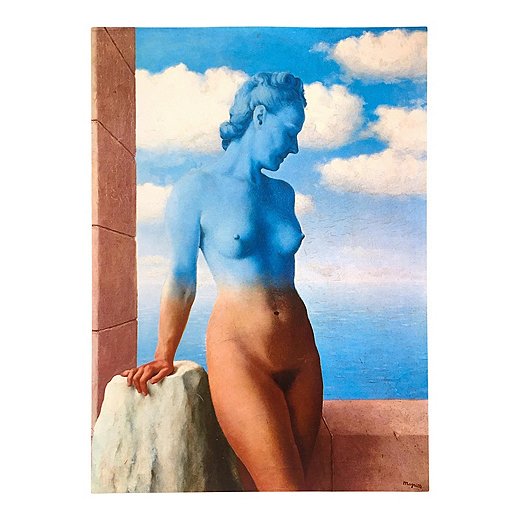

Magritte’s wife, Georgette, was the model for Black Magic, 1945.

A Few Facts About René Magritte

• The Son of Man, the painting in which an apple obscures the face of a hatted man, is a self-portrait. This wasn’t the first Magritte portrait that hides the subject’s face: Not to Be Reproduced, for instance, shows poet and art patron Edward James gazing into a mirror, but the mirror reflects the back of James’s head instead of his face.

• Not only were bowler hats prominent in Magritte’s paintings, but he himself frequently wore one. In his works they represent the generic and the anonymous; as to why they were his headwear of choice, “I am not eager to singularize myself.”

• Magritte’s earliest paintings, from 1915 to the early 1920s, were impressionistic. He returned to this style during the final years of World War II, creating works reminiscent of Renoir in terms of palette and brushstrokes. And for a brief period of 1948, he produced a handful of expressionistic paintings.

• Also during the German occupation of Belgium and after the war, Magritte is believed to have forged works by Picasso, Max Ernst, and Giorgio de Chirico, among others. Some sources contend that he forged currency as well at this time. Ironically, more than 50 years later—and 31 years after Magritte’s death in 1967—Belgium put the artist on its 500-franc banknote.

Shop Magritte prints >

Shop all art >

Eternity, 1935.

Join the Discussion