Black Americans make up only 2.3% of the interior design industry in the U.S. and 2.8% of architects, despite accounting for 12.1% of the population. This lack of representation in the 21st century makes the milestones of Black designers and architects in centuries past all the more impressive. Below we look at five Black industry pioneers.

Thomas Day

With curves both exaggerated and sleek, much of Thomas Day’s furniture is of a piece with today’s trends. But Day’s distinctive incorporation of negative space, use of mahogany veneers, and development of what became known as “Exuberant Style” are not the only reasons his furnishings are on display in museums nationwide. Born in 1801 to a free Black family, Day was arguably the first Black furniture maker in the United States to gain renown among a white clientele. At one point his North Carolina workshop accounted for 11% of the state’s furniture market; he took commissions from North Carolina governor David Reid and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, among others. Even so, when the Panic of 1857 led to a national economic collapse, Day—unlike his competitors—was unable to collect the money owed him by his white clients, simply because he was Black. His company went bankrupt, and Day died four years later, in 1861.

Both pieces shown here, at the North Carolina Museum of History, are by Thomas Day. The front design is one of his most famous: the Day Bed, notable for its use of negative space. Photo: Daderot/Wikimedia.

Sarah E. Goode

Before there was the Murphy bed, there was the Goode cabinet bed. Sarah E. Goode patented her design for a bed that unfolded from a roll-top desk in 1885, making her one of the first Black women to receive a U.S. patent. (For a while Goode was thought to be the very first, but archivists now believe Judy Reed preceded her with her “dough kneader and roller.”) Goode conceived of the bed to solve what was a common problem among the customers of the furniture she and her husband are thought to have owned in Chicago in the 1870s or so: a severe lack of space in tenement apartments. Little else is known of Goode, other than that she was born into slavery circa 1855 and died in 1905. None of her beds are known to still exist, and a photo commonly identified as Goode online is actually that of a Sarah Goode Marshall, a white woman said to be the first handcart pioneer to enter Utah’s Salt Lake Valley. Goode did receive some very belated recognition in 2012, however: The Chicago public school system named the Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy after her.

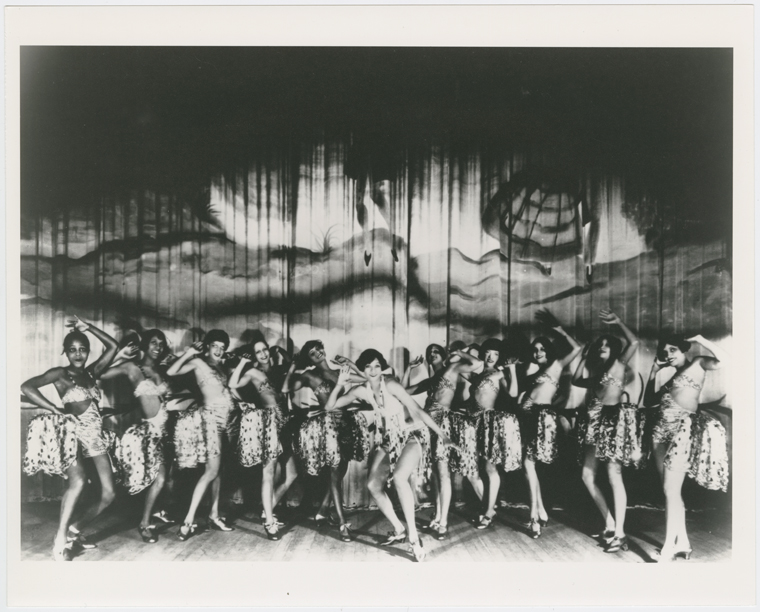

Maude Russel and Her Ebony Steppers at the Cotton Club, decorated by Harold Curtis Brown, in 1929. Photo: New York Public Library.

Harold Curtis Brown

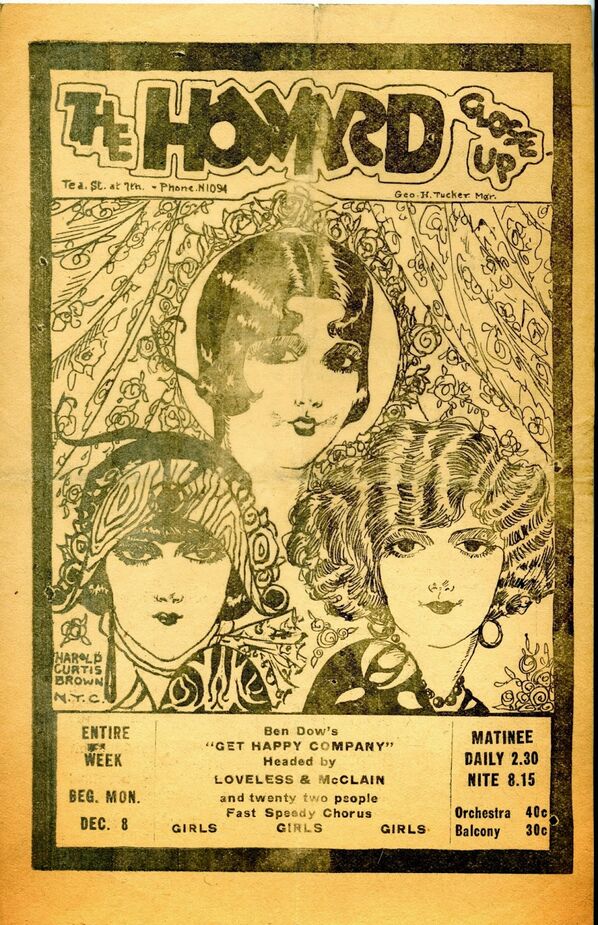

An illustrator as well as an interior designer, Harold Curtis Brown often appears on lists of “designers you need to know.” Yet very little is actually known of him. He studied at the Boston School of Fine Arts and New York’s New School of Design and with Lorenzo Harris, who created elaborate sand sculptures on the beaches of Asbury Park, NJ. Brown worked as an illustrator and a graphic artist, as well as owned an art shop, before focusing his energies on interior design, making him one of the first Black designers—let alone Black gay designers—in the U.S. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s he gave nightclubs such as the Cotton Club and Tilly’s much of their glamour and dazzle.

Brown decorated private homes as well. One person who wasn’t a fan: famed photographer (and infamous racist) Cecil Beaton, who crashed a party at the home of Brown client Jay Clifford and mocked, among other elements, the faux ivy that encircled the foyer’s steam pipes. Brown got off lightly; Beaton derided the host and his guests in print so viciously that Clifford sued him. The result of the suit is unknown.

Also unknown is anything about Brown’s life and career after 1938, though author/historian Michael Henry Adams makes a strong case that Brown decided around that time to pass for white and work under a different name.

A 1924 theater program illustrated by Harold Curtis Brown. Photo: Henry P. Whitehead Collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

In addition to creating the Beverly Hills Hotel’s Crescent Wing, Crystal Ballroom, and poolside cabanas, Paul R. Williams designed the logo and its type font still used today. Find this framed Slim Aarons print here.

Paul R. Williams

Unlike most of the others on this list, the life and work of Paul Revere Williams is well documented. Born in 1894 and a lifelong resident of Southern California, he became in 1921 the first Black certified architect west of the Mississippi and in 1923 the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects.

In addition to being a Black trailblazer, Williams was also a father of Los Angeles Modernism, though he designed homes in just about other style. Clients such as Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart, and Lucille Ball earned him the sobriquet “Architect to the Stars.” Nonetheless, he worked with another Black architect, Hilyard Robinson, to build the Langston Terrace Dwellings in Washington D.C., one of the country’s first federally funded housing projects, and he designed churches, schools, hospitals, hotels, restaurants, and government buildings as well—more than 2,000 buildings during his 50-plus-year career.

Williams employed an in-house team of interior designers to ensure his vision, and that of his clients, extended throughout his clients’ homes. Leading the group beginning in the 1950s was Norma Harvey, one of Williams’s daughters. Her artistry as well as that of Williams was seen by millions nationwide in 1956 when Frank Sinatra gave a live tour of his Beverly Hills home on Edward R. Murrow’s Person to Person TV series.

Cecil Hayes (shown at left) gained acclaim for designs that embraced color and global influences, such as the one above. Photos: @cecilhayesofficial.

Cecil Hayes

Credited as the first Black designer to be featured in Architectural Digest, Cecil Hayes also became, in 2000, the first Black designer to be named to the prestigious AD100 list of the world’s most influential architects and designers. Hayes made the AD100 several times since, wrote two design books, and beautified the homes of Samuel L. Jackson, Wesley Snipes, and Timbaland, among others. Born, raised, and based in Florida, Hayes worked as a teacher before becoming in 1971 one of the first Black students at the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale. Two years later she was working at a design firm; two years after that, Hayes opened her own practice, Cecil’s Designers Unlimited, which she ran until a few years ago. In 1983 she and her husband began designing and manufacturing their own furniture—in a sense, harking back to Thomas Day and Sarah E. Goode.

Join the Discussion