Peter leans opposite his favorite pieces—a pair of 1950s Italian zebra-stripe chairs.

One of the perks of Peter Benson Miller’s position at the American Academy in Rome is an apartment that spans the floor of a Neo-Renaissance villa. Since his position typically has a three-year tenure, when he and his partner arrived “the space felt like a short-term faculty apartment,” albeit one furnished with Piedmont mirrors and antique sideboards. Peter, an art historian and curator, set about transforming it with heirlooms from his parents’ Pennsylvania home, pieces he’s collected during 20 years of living in Rome, and his own daring design sensibility. As he puts it, “I’m drawn to postwar Italian and French design, but I only really have the money to pick up things at flea markets and junk shops. So I guess this apartment has a sort of junk-shop aesthetic.”

Discover how, in Peter’s deft curatorial hands, his uniquely Roman home inside the storied academy sings with refinement, beauty, and just a touch of punk.

The home’s photography collection includes work by Malian photographer Malick Sidibé and Italian photographer Nino Migliori.

The porcelain plates painted with black-and-white faces are by Milan designer Piero Fornasetti.

Finding a Happy Arrangement

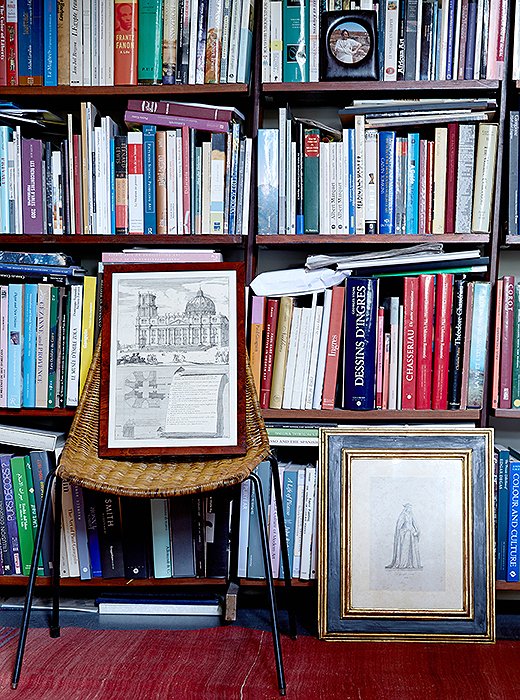

Peter wanted this home to feel lived-in and layered, much like Rome itself, and for anyone—but especially for a curator—hanging art goes a long way to making a home one’s own. The apartment “didn’t have any art to speak of,” Peter says, so he brought in his own collection. Hanging the pieces, to Peter, means allowing the art to dictate where it should go. “When you’re first hanging a show, you lean things against a certain wall, and then come back to see if they work. I do that at home,” he says. “When you put them on the wall and it becomes definitive, you stop looking at them. I like things to move around and let them yell at me.”

Similarly, Peter doesn’t settle for a straightforward arrangement of objects; he searches out the witty little juxtaposition or the piece that turns tradition upside-down. For instance, a stately Florentine Neo-Renaissance mirror, which was already hanging in the entrance hall when they moved in, became a resting spot for a little owl from an Umbrian junk shop.

The first piece placed in the apartment was a beloved sofa, upholstered in linen block-printed with pomegranates and vines. Over the doorways, Peter hung a pair of mosque shields found in the Anatolia region of Turkey.

The red in this Turkish rug works with the red on the sofa—as well as the hot red of the ceramic piece atop the highboy.

Getting Schooled in Design

Although a worldly curator in his own right, Peter credits his parents—along with the heavy influence of Rome—for the style he brings to his home and work. “They compellingly mix things like 18th-century furniture and contemporary art and think nothing of it,” he says. To Peter, switching up the conventional context can serve to highlight favorite pieces, subtly freshening up the traditional look. Needlepoint cushions inherited from his grandmother sit front and center on his beloved living room sofa—“in the context of a living room full of contemporary art, they look a lot hipper.” In the same living room, Peter put a fire-red ceramic piece—an old plaster cast of a soup tureen—on top of a traditional highboy. “It takes the highboy down a notch, makes it less serious. I like to find that intersection between punk and good taste.”

Peter adores white vases designed by Constance Spry, whom he describes as “the Martha Stewart of 1920s England.”

Above a settee hang a split-in-two image by Italian artist Gianluca Malgeri and an image by Indian photographer Dhruv Malhotra, who wanders the New Delhi streets at night photographing people sleeping.

When you put art on the wall and it becomes definitive, you stop looking at it. I like things to move around and let them yell at me.

Even in the narrow kitchen, the apartment feels villalike with its soaring arches and long windows.

The kitchen scale was a gift from the owners of a favorite Campo Fiori grocery store, where Peter and his partner used to buy fresh ricotta and prosciutto before it closed.

I like to find that intersection between punk and good taste.

A Venetian bed in the library is perfect for guests in a pinch. Over the bed is a work by Daniela Edburg, which goes beautifully with the embroidered poppies on the pillows.

Life on the Hill

If you know of the American Academy in Rome, you’ve probably fantasized about taking up residence there. Each year it opens its doors to 30 new fellows—American artists, writers, scholars—who come for the promise of uninterrupted, peaceful focus. As the Andrew Heiskell arts director of the academy, Peter ensures that half of the fellows have all they need. “I support them—help them find resources, do studio visits—and give them a shoulder to cry on, though there’s not much of that, since everyone’s very happy to be here.” On top of that, he helps plan the 30 events the academy hosts annually—a recent one was a reading by Sally Mann from her new book, Hold Still—along with exhibitions, such as this past fall’s show of photographs by Cy Twombly, the American artist who had long lived in Italy.

Meals come from the Rome Sustainable Food Project, which Alice Waters dreamed up just for the academy (think picked-moments-ago produce and a divinely light take on Italian food). “The academy is unique in that the community eats together twice a day—it’s not required but everyone goes because the food’s so good!” Peter says. “It’s a wonderful way to exchange ideas. Being here is about being interdisciplinary and collaborative and seeing one’s discipline from different points of view.”

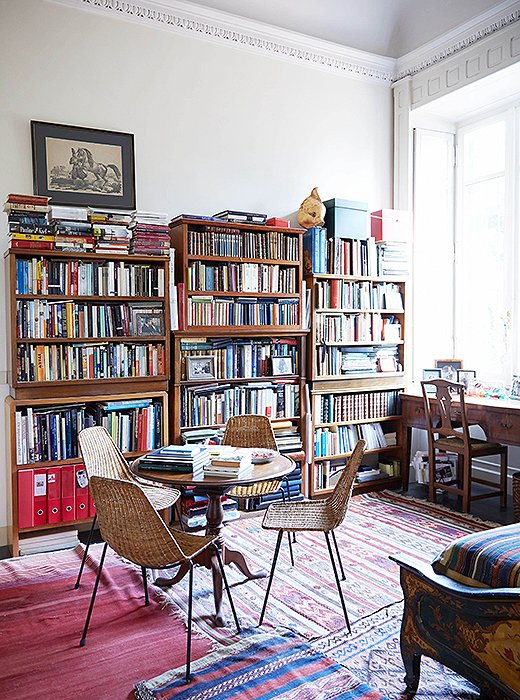

One of the layered rugs was the first thing Peter ever bought with his own money, during a trip to Turkey’s Aegean coast when he was 14. The rattan café chairs from the 1950s are paired with an 18th-century table from his parents.

Peter reclaimed bookshelves from Italian ministries of the 1930s and ’40s and filled them with his books. As well as reading a lot for work, he loves the chance to relax with everything from Jane Austen to Junot Díaz.

A 1990s lithograph by American artist Robert Longo leans behind another assemblage of white vessels.

Above the guest room bed hangs a photograph by Olivier Roller of a bust of Lucius Verus, who was co-emperor of Rome with Marcus Aurelius.

On top of the guest room armoire, Peter perched an aluminum boat that he and his partner found at a junk shop.

Savoring Downtime

With an intensely social job, Peter uses any pockets of time to keep up with friends outside the walls of the academy. “We try to lure our friends up the hill to dinner,” he says. “There’s no tradition of hard liquor in Italy, so cocktails are prosecco, or champagne if we’re feeling flush.” Peter adds that you never need to specify when to come for dinner. “If you’re invited to dinner in Rome, you know not to come until 8:30 or 8:45 p.m. and that you’ll sit down to dinner at 9:30 p.m.”

Of this bathroom’s rounded shape—which gives it a chapellike atmosphere—Peter says, “This space was originally a servant’s staircase. Now when you’re lying in the bath, you can see the round opening up top.”

Peter collects aquarium-esque sculptures by Alfredo Barbini, a Venetian glass artist who worked in the 1940s and ’50s.

By the hallway to the garden, Peter arranged a tableful of objects—a French plaster cast of the foot of the Apollo Belvedere, Neapolitan pinecones made of terracotta, and a papier-mâché alligator wearing an emerald necklace.

This portrait of Peter’s grandmother as an eight-year-old was painted by her aunt, Anna Ingersoll, who often traveled to Italy. “It’s all her fault that I ended up living here!” Peter says.

Peter on the steps to the garden behind the villa, which spans a hectare (just shy of two and a half acres).

Settling In

Peter seems remarkably settled in the Roman life he’s built. But whenever they have a chance, he and his partner decamp to their country home in Puglia, which they’ve spent seven years putting together, to garden and decompress. “There are difficulties, of course,” Peter says, “but all in all, for the things we look for in the place we live, Rome is the right place for me.”

Join the Discussion