Bethann Hardison is known for her role in fashion, but her apartment is a decided departure from the term. There is nothing of the now in the Deco-era space in New York City’s Gramercy neighborhood, and she firmly admits to having no real interest in decorating. That does not mean her home is void of style, however. It is full of it.

One of the first African-American supermodels, Hardison began her career in the 1970s. Milestones include walking in the landmark Battle at Versailles Fashion Show, running her own modeling agency, and founding the Diversity Coalition with Iman and Naomi Campbell. There is also the documentary Invisible Beauty, which she produced and directed spotlighting the relationship between black models and the fashion industry, and there are the many letters she’s penned to designers and editors advocating for diversity on the runway and the page.

Hardison’s two-bedroom home is not a reflection of any particular aesthetic or image but of originality—a word that Diana Vreeland used to distinguish between those with style and those without. It is, simply put, a reflection of Hardison herself—a collection of things that speak to the people she’s met and what she’s done with her life so far. In the living room hangs a mixed-media piece from friend Keith Haring, which he gave her the night he first discussed his battle with AIDS. Above it hangs a painting by David Bowie (also a gift), and across the way, sitting in a glass cabinet, rests a pair of custom Hervé Leger shoes, which she wore as the maid of honor at Bowie’s wedding to Iman. There are bookshelves packed with books, most of which she hasn’t read, but they are there and there is room, so why purge?

When asked about her advocacy work and when it began, Hardison pauses before responding. “I don’t know when I started to consider myself an advocate,” she says, “but I do believe I’ve always had a calling. There’s always been some kind of revolution inside of me wanting to come out.”

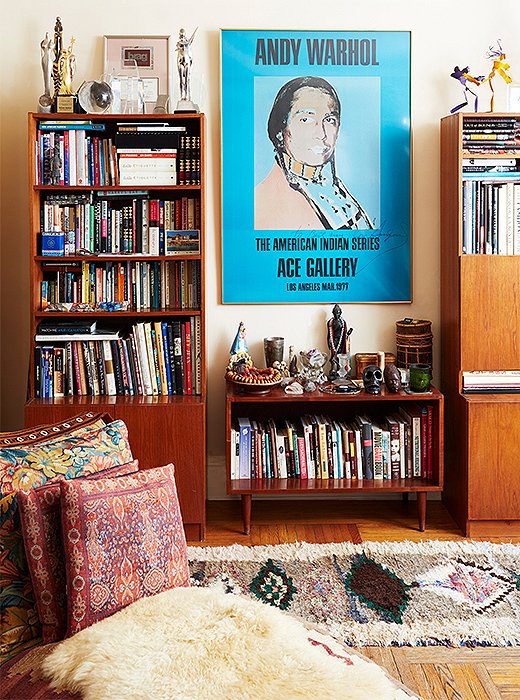

Worth noting is that she says this while sitting at her desk, facing a wall where a poster from Andy Warhol’s American Indian series hangs. Gifted by Warhol, it depicts Russell Means, a member of the Oglala Lakota people of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota who is best known for his leadership during the occupation of Wounded Knee. More than adornment, it serves as a reminder not only of the friend she used to lunch with at The Factory but also of the work that matters to her most. “I never cared about all the celebrity stuff that [Andy] did,” Hardison says, “but that guy… he was a real gangster with a cause.”

Below, take a closer look at the storied space and be inspired by the woman it serves as a portrait of.

A wall of art features work by David Bowie and Keith Haring (both of whom were close friends of Hardison’s) and a number of paintings from Haiti. Two Thai benches flank the desk and were once used in the office of Bethann Management, the modeling agency she ran for 12 years before closing it in 1996.

African sculptures grace the entry’s console table, beneath which sit baskets collected from near and far. “I’ve always kept my savings for travel,” Hardison says. “Travel is important.”

A trio of black-and-white photographs hang above a carved wooden chair, next to which stand two stools, artfully stacked to serve as a side table.

Religious figures found while traveling intermingle with Hardison’s sizable jewelry collection.

A poster depicting Russell Means keeps watch over the living room. Shelves are packed with many books she admits to never reading, but Some of Me, written by close friend Isabella Rossellini, is a continual source of inspiration. “You read it and you feel like you’re talking with a friend,” Hardison says.

Left on view, Hardison’s bike takes on a sculptural quality in front of the fireplace.

Photographs and mementos hold court on the mantel.

A vintage vanity plays host to more of Hardison’s jewelry, left on display but organized by way of baskets and bowls.

Figures found while traveling stand on top of a cabinet. Some were found in Mexico, where Hardison has two other homes, and represent her affinity for the country and the culture she’s experienced there. “You’ve got to have something from Day of the Dead,” she quips.

Bethann Hardison enjoys the moment, at home.

I don’t know when I started to consider myself an advocate, but I do believe I’ve always had a calling. There’s always been some kind of revolution inside of me wanting to come out.

Join the Discussion