Interior design is one of the relatively few fields in which women made their presence felt early on. Decorating homes was of course long considered part of the domestic arts and therefore under women’s purview. Unlike other “women’s work,” however, women were able to monetize it right alongside the men. It became one of the few professions considered acceptable for well-bred women beginning at the end of the Victorian era.

Just as important, women were at least as influential as men when establishing trends, styles, and guidelines that are still apparent in homes today. Below we tip our color wheels to a few of the earliest female decor innovators.

A portrait of Madame de Pompadour by Maurice Quentin de la Tour; note the green-and-pink color scheme and the ornamented furniture.

Madame de Pompadour (1721-64)

This mistress of King Louis XV is probably best known for the upswept hairstyle that bears her name. Or perhaps you’ve heard the legends: that the original champagne coupe was modeled after the shape and size of one of her breasts, that the first marquise-cut diamond was inspired by the shape of her lips. But Madame de Pompadour was also a patron of the arts, an accomplished printmaker, an engraver of precious stones, and a major proponent of rococo style. She frequently redecorated both her own château and her quarters at the king’s various estates, making the heavily ornamental “more is more” look de rigueur among tastemakers. She was also instrumental in the founding of the Sèvres porcelain factory; one of the manufacturer’s signature colors, debuting in 1757, is rose Pompadour.

Elsie de Wolfe (1859-1950)

A socialite and an actress, Elsie de Wolfe is sometimes incorrectly credited with being the first professional interior designer in the United States. She wasn’t even the first female professional decorator in the country; Candace Wheeler co-founded the interior design firm Tiffany & Wheeler with Louis Comfort Tiffany, of Tiffany lamps fame, in 1879. But de Wolfe was arguably the first celebrity designer. Her clients included the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and industrialist Henry Clay Frick; just the 10% commission she received on items that Frick purchased on her recommendation in 1913 made her, she wrote in her autobiography, After All, “tantamount to a rich woman.” De Wolfe played a major role in persuading Americans to abandon the dark, heavy Victorian aesthetic in favor of airier, lighter spaces. She loved beige, chintz, wicker, large mirrors, and chaise longues. Many of her innovations have stood the test of time, as has much of the advice in her book The House in Good Taste. In fact, with tips such as “Don’t go about the furnishing of your house with the idea that you must select the furniture of some one period and stick to that,” de Wolfe showed herself to be one of the first advocates of the “mix, rather than match” sensibility we love. No wonder we named the One Kings Lane elephant icon Elsie in her honor!

A painting of Elsie de Wolfe’s bedroom by British artist William Bruce Ellis Ranken.

Syrie Maugham (1879-1955)

Just as influential as de Wolfe, and just as well connected socially, Syrie Maugham numbered Jean Harlow, Noël Coward, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Babe Paley among her clients. In revolting against Victorian dreariness, she went even further than de Wolfe, favoring rooms dominated by white. In the London home she shared with her then-husband, writer W. Somerset Maugham, she dramatically unveiled at a late-night party in 1927 her all-white music room: Walls, curtains, furniture, even the flowers were completely white. In another of her homes, she decorated a salon exclusively in beiges, except for pale pink satin curtains. In addition to monochromatic schemes, Maugham favored minimalist rooms with pops of jewel tones. And let’s not forget some of the hallmarks of Art Deco interiors that she helped popularize: fringed sofas, chrome, room screens, shagreen, and pickled and painted woods.

Dorothy Draper (1889-1969)

Another socialite-turned-designer, Dorothy Draper owes more to Madame de Pompadour, stylewise, than to de Wolfe and Maugham. She described her style as “modern baroque,” and one could say she went for broke/baroque when it came to layering bold colors and large-scale prints, particularly florals. She hit her stride in the 1930s, her designs for New York’s Carlyle and Sherry-Netherland hotels an exuberant counterpoint to the continuing Depression. During this time she also wrote a syndicated newspaper column, and the title of her 1939 book, Decorating Is Fun!, summed up her philosophy. After World War II she was charged with transforming the 19th-century Greenbrier hotel into a 20th-century pleasure palace.

A lounge at the Greenbrier exemplifies the Draper style: layers of bright colors and vivid patterns. Photo by A.D. Maust/Wikipedia.

Madeleine Castaing (1894-1992)

Like Draper, French decorator Madeleine Castaing was a maximalist. In keeping with the crowd she ran with—Erik Satie, Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso—her preferences were more outré than Draper’s, however. If you’ve ever covered your floor with a leopard-print rug, you can thank Castaing. (Her reasoning for choosing the print was practical as well as aesthetic: She liked that it hid dirty footprints.) Other elements of what is now called style Castaing include banana-leaf wallpaper and the juxtaposing of multiple jewel tones, including a distinctive take on sky blue named in her honor, accentuated with glossy black.

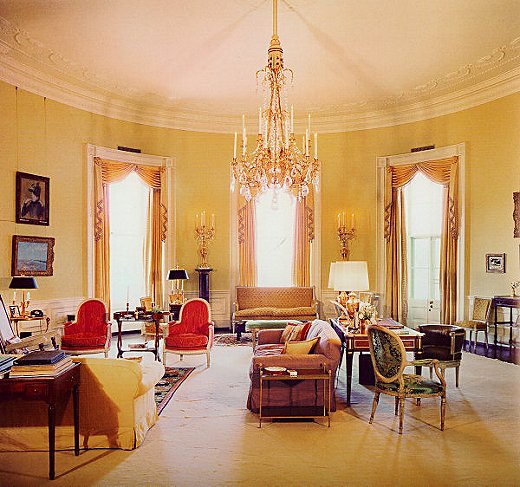

The Yellow Oval Room in the White House, as decorated by Sister Parish during the Kennedy administration.

Sister Parish (1910-94)

Née Dorothy May Kinnicutt (and a cousin of Dorothy Draper), “Sister” Parish is credited with creating American country style: incorporating rag rugs and needlepoint pillows, patchwork quilts and wicker baskets, botanical prints and painted floors, chintz fabrics and whitewashed furniture. Despite the “American” label of her style, though, Parish had no qualms about integrating Old World elements, from Murano chandeliers to Regency chairs. Just as important were the seemingly unstudied furniture arrangements. In a Sister Parish room—even in the White House, some of which she decorated for the Kennedys—you could move a chair or clear a space on a coffee table without feeling as if you were destroying something precious. One could say she elevated insouciance to an art form.

Join the Discussion